“Women are not small Men. Stop eating and training like one”

This series will start on this note hoping to reach all female athletes, be it a Mom trying to get back into exercise, a weekend warrior who does adventure races and cycles, a daily CrossFitter, or a professional athlete, as well as their female and male coaches.

We like to think that progress is being made in sports science on how best to prescribe exercise, but the reality of the situation is, we are still arguing over growth plate issues in children even though the evidence is clear and numerous studies have put this issue to bed, we are failing miserably as a profession to distinguish between women and men when it comes to training.

Why is this? After all, there is a whole list of evident musculoskeletal, physiological, and endocrine differences between the two genders.

Are we missing the extremely obvious and important fact that women are in fact women and men are in fact men?

If we were to tailor training programs accordingly, what would they look like?

Research is clear that coaches should be considering the female’s unique physiology in order to design a proper and beneficial training program. When compared side by side with men, women, undeniably, might have some disadvantages on the physical performance field.

For example, the hormones which tell our bodies when to eat, sleep, grow, and many other basic needs are pretty constant in men; however, in women, the situation is somewhat different and that is centred on the menstrual cycle (Sims, 2016).

What are those differences, and how do they impact in Sports performance?

Musculoskeletal:

Women tend to be smaller, lighter, and have more body fat than men. If you were to peel off the layers of skin and guess if the muscle system you are looking at were male or female, you wouldn’t be able to tell right away. That said, men and women generally have the same muscle composition when it comes to the percentage of Type I endurance (aerobic) fibres and Type II power (anaerobic) fibres, an important difference is that the largest fibres in men tend to be the Type II power fibres, while in women, they tend to be the Type I fibres.

When it comes to storing fat, women are surely the winners. Essential fat in women, because they are designed to give birth, is about 12%, while in men is 4% (Sims, 2016).

This essential fat is not only nerves, bone marrow, and organs, but also includes the breasts that are mostly made up of fat tissue.

Hormonal Influence:

Testosterone, a primary male hormone, contributes to bone formation, protein synthesis and leads to larger bones and muscles, Oestrogen, a primarily female hormone, is quite efficient at fat deposition and is an inhibitor of anabolic stimuli (i.e: growth), leading to more fat mass and an inability to make muscle. It is important to keep in mind that oestrogen (and progesterone) will fluctuate during the menstrual cycle. Some studies suggest that during the follicular phase muscles’ diameter increase (Pitchers & Elliot-Sale, 2019).

Keep an eye out for the upcoming information series we are putting out on the female athlete triad and other considerations for females training.

Also, according to numerous studies, including one by Reed, et al (2008), oestrogen and progesterone changing levels throughout the cycle can cause symptoms such as: depression and anxiety, asthma, cramping, bloating, and gas. All these symptoms can, directly or indirectly, easily affect overall wellbeing and consequently, sports performance.

Strength, Speed, and Power:

Even though research studies’ results can slightly differ on the exact percentages, it is unanimous that men have more upper body strength and women have more lean muscle tissue below the waist. A female’s absolute whole-body strength (1RM), upper body strength, and lower limb strength is: 60-63.5%, 55% and 72%, respective to of a man’s (Pitchers & Elliot-Sale, 2019). However, sheer and absolute values comparing strength relative to body weight, fat-mass, and muscle cross sectional area, a woman’s lower body strength is similar to a man’s.

Research data also shows no difference in muscle synthesis post exercise suggesting that a strength training programming for females can follow the same principles as that of a male counterpart.

This means that relative strength and hypertrophy is very similar; men just have more muscle available.

Cardio and Endurance:

Possibly somewhat of a surprise is, women have a smaller heart. Not only smaller in organ size, but also a smaller heart volume, smaller lungs, and lower diastolic pressure (heartbeat that pumps blood to the whole body).

This can cause women be more susceptible to dehydration in the heat. Since less oxygenated blood travels the body per beat, in order to deliver more volume, the heart needs to beat more often and the respiratory muscles work harder. On top of that, men have 10-15% more hemoglobin than women. Hemoglobin molecules are the carriers of oxygen in red blood cells. Combining all this information, women’s smaller hearts and lower oxygen-carrying ability makes them have a lower max VO2 (how much oxygen can be used during exercise).

During aerobic exercise, due to the high levels of oestrogen in high hormone phase, women tend to rely less on carbs and more on fat.

This can become a problem when trying to hit high intensities and there is not stored glycogen to fuel the anaerobic energy system.

Take note female athletes (And any female CrossFit/Mixed Modal athlete in particular), your monthly cycle and fuelling strategies around competition day matter.

Recovery:

Although women tend to efficiently use their Type I fibres, they mobilise more fat while exercising and to store it when recovering.

When oestrogen levels are high, women struggle accessing stored carbs to rebuild muscle and progesterone increases muscle breakdown. This means that on a high hormonal level, it becomes harder to build muscle. After a hard training session, a more intentional recovery should follow.

Again, keep an eye on upcoming pieces we are writing and recording on how to shape your training depending on your monthly cycle. We also cannot recommend an amazing app developed right here in Ireland for female athletes called “Fitr Woman” that can help female athlete’s and their coaches plan micro and meso cycles of training around the menstrual cycle.

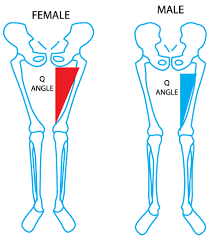

Women’s “Q-Angle”, the angle between quadriceps muscle and the patellar tendon that contributes to proper traction of the knee, can be heightened during the menstrual cycle (widening of the hips).

Knees and ankles, along with the propensity for women’s joints to be hypermobile, contribute for an increased risk of injuries. In fact, research has suggested that women are up to eight times more likely than males to sustain a knee injury, in part due to hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle (FitrWoman).

Regarding breast health, since breasts have limited internal anatomical support, specialists recommend that a ‘good’ sports bra should have a wide vertical adjustable strap, ensuring the back has adjustability but not elastic and able to provide comfort and support suitable for the exercise intensity (Burbage, 2019). A poor support can cause irreparable damage and increase the likelihood of breast ptosis (Pitchers Elliott, 2019).

Environment:

Women’s unique physiology will, on a very individual basis, impact interaction with the environment. Body size, blood volume, and metabolism will, for example, impact thermoregulation, which is the body’s ability to maintain a consistent core temperature.

Also, women start sweating later and overall sweat less – keeping them hotter than men, especially on a high hormone phase. The main reasons are oestrogen and progesterone, once again controlled by the menstrual cycle.

Again, there are considerations here for both menstruating females and those in the menopausal phase.

Although there is not conclusive research regarding it, hormonal contraceptives that ideally are used for their main purpose, and not for menstrual cycle control, can positively and negatively (and sometimes randomly) affect all the hormonal spells on the body, including improved skin and weight gain (Martin et al, 2018).

In Conclusion:

Women are not men, but they can certainly train as hard as men do.

It is incumbent upon every coach who works with females to learn about and to work with their unique physiology starting even before puberty.

We have seen female athletes lose and miss periods due to overtraining, excessive fatigue and body fat levels which are too low.

This can and should be avoided if we understand what intervention is causing this and look to remedy this.

In order to individualise and adjust training, recovery, and performance, these differences should be considered. Hormonal fluctuations during the menstrual cycle can biomechanically alter the female body and there is a great need to understand its dynamic and its impact in sports.

I’m a coach or parent of a female athlete, does any of this really matter?

There are many examples of sports organisations improving the periodisation (that is the planning of training) for females. One of the most successful female sporting organisations on the planet, US Women’s Soccer, in 2019, attributed much of it’s success due to their menstrual cycle monitoring and since then, more and more athletes and coaches have been sharing their life change decision of simply tracking their menstrual cycle as one of the most important metrics to look into. Understanding the implications of female anatomy on sports performance and how to better train and fuel the female body is a fundamental aspect of coaching the female athlete that has until now gone largely ignored. Understanding the subtleties and interplay in all these areas could change a game, or better still change a life.

As mentioned earlier, we plan to dive deeper into how best to understand your training around the menstrual cycle and unlock better performance, and more realistic expectations around intensities at each stage of the month.

“The fact is, female athletes are biologically, hormonally and physically different, and the sooner that reality is embraced instead of resisted, the more potential exists for that athlete to optimise her training behaviours,” Dr. Jennifer Ashton

The lay person coach looking after an underage female team right up to the highly qualified sport scientist looking after an Olympics bound female athlete needs to start realising and unlocking the potential in female athletes, if we do this we start to treat female athletes with the utmost respect they deserve and we start to stem the tide of females dropping out of sports at an early age.

It’s all our responsibilities.